Teenage Dreams: Girlhood Sexualities in the U.S. Culture Wars (2022) is a well-researched, readable academic perspective on the political and cultural shifts taking place in the US during the past 40 years, and how race- and class-based discomforts about the sexualities of teenage girls have been used to push conservative political agendas over this time. Jeffries also explores how teens and their adult accomplices have resisted political instrumentalization, advocating for accessible sexual health information and healthcare, issues which continue to be relevant to our current political landscape. I had the pleasure of getting to ask Jeffries some questions about her process, her current research, and how topics she discusses relate to ongoing culture wars today.

Ki Niehaus: I was a white queer teenage girl in the US in the 2000s, and reading Teenage Dreams helped me understand some of the contradictions around teen sexuality that I experienced personally. Pushing to delay sexual activity as long as possible, or to limit the total number of partners one had, were staples of how I remember otherwise comprehensive sex education being taught, and you skillfully weave together how cultural and political forces came together to produce an ambivalent and restrictive approach to teen sexuality that even left-leaning people were happy to co-sign. Did you have any similar moments of personal recognition or understanding while researching and writing this book?

Charlie Jeffries: Thank you for sharing that—I definitely had some of those moments myself while writing the book, despite the fact that I moved to the UK from the US when I was 11. Researching the book did drive home differences in American and British attitudes towards youth, gender, and sex, and the different material realities facing teenagers in each context, but there was still a lot which resonated with my experience of being a teenager in the UK. In particular, the racialized and classed emphasis in American political discourse in the entire period the book covers on the connection between sexual and reproductive behavior in youth and a young person’s socio-economic future. That was also a pervasive feature of how adults talked about and to teenagers in the same period in the UK, despite the wider availability of comprehensive sex education here; it’s a neoliberal rather than strictly American ideology.

Some of what I found in my research for Teenage Dreams chimed with my memories of those events from the period when I did live in the US as a child. For instance, in chapter four I discuss how media coverage of Bill Clinton and Monica Lewinsky led to a lot of young people hearing explicit conversations about sex in the media for the first time, something that teachers and parents then had to contend with. Researching that moment made me understand why, as a young person, it had felt so unusual to hear discussions about something so personal alongside presidential politics, and to see that kind of terminology on the front page of newspapers for the first time.

KN: It was incredibly cool to learn about activist groups and individual teenage girls advocating for themselves and their own sexual health needs and rights during this time period. Another theme of Teenage Dreams is the adults who were allies to these teenagers, in contrast to others who were pursuing more restrictive and politically conservative agendas. Can you say a bit about what this kind of advocacy or allyship from adults toward teenagers looked like?

CJ: Absolutely—I’m so glad you enjoyed reading about those individuals and groups. Support for teenagers’ own advocacy takes a lot of different forms in this story. One of the main histories I wanted to highlight in this book was the long-running action of young people against punitive and dangerous policies, and another key history here is that of the adults who resisted the dominant position in the political mainstream—amongst conservative and liberal factions alike—to deny teenagers access to sexual information, reproductive healthcare, freedom of gender and sexual expression, and other rights. At some moments in this history, this was characterized by adults using their own resources and activist networks to set young people up to have the mic—such as the SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective’s 2007 conference in Chicago, with the theme ‘Let’s Talk About Sex’, in which youth activists’ voices were made central to the event, and informed adult organizers’ learning on the day. At other times, allyship took the form of distributing sexual information to teenagers in a country where sex education was becoming increasingly hard to access, despite the risks involved—like the adult editors of the glossy teen magazine Sassy did with their publication in the 1990s, until an advertiser boycott led by a conservative group led to it having to shut down. These are just two blueprints that this history can provide of how we can show up for young people during periods where their rights and lives are under attack.

KN: You talk about the rhetoric of this time as ‘stuffing’ teenage sexuality back into childhood, and you also discuss how young adults were sometimes also included in conversations about teenage sexuality. These appeals to parental fears around teen behavior were used to enact legislation that also ended up affecting adult access to reproductive healthcare. While similar patterns continue in the US around reproductive rights, do you see some of these rhetorical strategies playing out in current US culture wars around LGBTQ+ and specifically trans youth’s access to healthcare and information as well?

CJ: Unfortunately, I absolutely do see a lot of the same kinds of rhetoric used in the contemporary US culture wars that appeared in 20th century history. In addition to current, explicitly conservative efforts to police young people’s gender and sexuality (such as the Don’t Say Gay bill), some liberals stipulate that they are in support of trans rights except when it comes to children’s and teenagers’ access to gender-affirming medical care. As you mention, this kind of position historically leads not only to harm to young people, but to the eventual erosion of the rights of adults, too. For instance, in the 1980s, many ostensibly progressive adults claimed that, while they believed that adult abortion rights should be protected, people under 18 should be required to notify or seek consent from their parents in order to obtain an abortion. This set up legal and social precedents in that era for limiting access to abortion that chipped away at the federal protection for abortion rights under Roe v. Wade, which of course was ultimately recently overturned. So I’m extremely concerned by the implications of recent policies targeting LGBTQ+ and trans youth across the US, and the way in which some liberal factions continue the historical pattern of making exceptions in their support for LGBTQ+ rights when it comes to those under 18, for queer and trans people of all ages.

KN: A consistent pattern in culture war fights in the US (and elsewhere) has been often white, class-privileged feminists partnering with right wing movements and politicians to advance a particular shared agenda, like efforts to ban porn in the 1980s or to advocate against information on sexuality being accessible to teenagers, both of which you discuss in the book. How do these alliances tend to play out, both for feminists who make such compromises, and for the political culture at large?

CJ: Badly, in both cases—the example you mention, of antipornography feminists attempting to advance their policy goals by joining with conservative efforts against ‘obscenity’ in the 1980s, led to Reagan’s right co-opting feminist language, research, and expertise, and gaining legitimacy from a wider audience. Those feminist groups, meanwhile, did not achieve their policy aims, and created or deepened huge schisms in feminist organizing as a result of their decision to work with factions of the right.

In terms of the wider political culture, I would argue that similar kinds of political compromises made by some feminists since the 1980s have perpetuated this pattern: opportunities for meaningful change for marginalized groups are lost, and the right learns more feminist language to either mock or misappropriate along the way.

KN: My favorite chapter of Teenage Dreams is Chapter 3, ‘Explicit Content: Cultures of Girlhood’, in which you explore Riot Grrrl and girlhood zine cultures in the 80s and 90s. You trace dominant players in these scenes that many readers may already be familiar with, like Kathleen Hanna of Bikini Kill and Le Tigre, but also explore grrrls responding to racism and homophobia inside and outside of the Riot Grrrl scene. Why did you choose to focus on zines, and what was your research process for assembling this chapter?

CJ: I’m so glad to hear that you enjoyed that chapter. Including young people’s musical subcultures of this era in Teenage Dreams emerged quite organically, as I was introduced to a lot of the bands and zines I ended up researching through the feminist and queer student activist groups I was involved with during my PhD. It was one of many moments in this project where cultural moments I was already drawn to or interested in ended up being a key part of the history I was researching.

Working with the zines that these communities created in the 1990s and 2000s was enabled by the fact that many of those involved in these scenes eventually formally archived their zine collections, and I was guided through these collections by zine archivists who are deeply knowledgeable of the material. The zine archivists I worked with also advised me on the ethics of researching in these collections: while they contain important sources that give glimpses into the emotional and political lives of teenagers in the past, researchers need to think carefully about what we should gain permission to put in print, etc. Chapter three was one of the chapters in this book which included the most voices of young people writing about their lived experiences in the late 20th century, and because of the recentness of this history, this meant a lot of consideration went into deciding what to include in the chapter.

KN: Last one: what are you working on currently?

CJ: I’m working on two projects: the first is an article about how the ‘campus wars’ of the 1990s—public battles over student and faculty activist efforts to make experiences of US higher education safer and more inclusive for people of colour and for women—marked a shift in usages of ‘free speech’ in American political culture. The way that college-aged activists are discussed in a lot of the media sources I’m looking at for that project shows a lot of crossover with Teenage Dreams.

The other project I’m beginning work towards will eventually be my next book—it’s on the American lesbian magazine Girlfriends (1993-2006), and what it’s history can tell us about the shift in queer politics from the disruptive direct action of AIDS activists in the 1990s to a more assimilationist model in the 2000s. I found a single copy of Girlfriends in an activist’s personal archival collection when I was researching Teenage Dreams, which led me to look at the entire run of the magazine, and I’ve been excited to start work on this ever since.

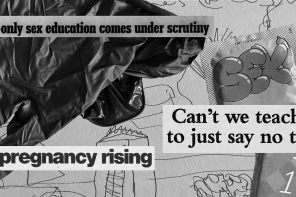

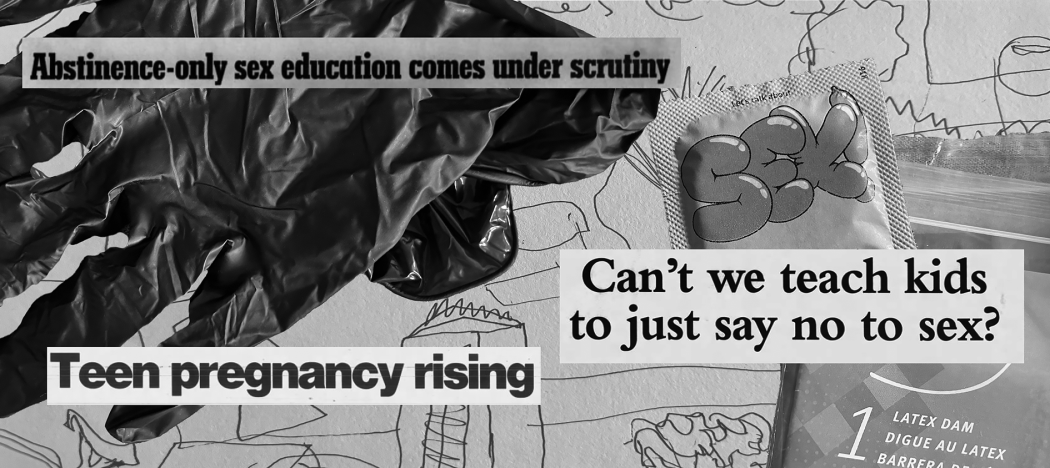

Header Image by Ki Niehaus

Charlie Jeffries (she/her) is Lecturer in American and Media Studies at the University of Sussex. She is a historian of sexuality and of social movements in the late-20th and early 21st-century US. She is the author of Teenage Dreams: Girlhood Sexualities in the US Culture Wars (Rutgers University Press, 2022), which won the Arthur Miller Institute First Book Prize from the British Association of American Studies in 2023, and the co-editor, with Sarah Crook, of Resist, Organize, Build: Feminist and Queer Activism in Britain and the United States in the Long 1980s (SUNY Press, 2022).

Her contact information and more details on her research can be found here: https://profiles.sussex.ac.uk/p580214-charlie-jeffries/about

Ki Niehaus is a multimedia artist, writer, and creative technologist living in Berlin. She enjoys thinking, writing, and making art about power, relationships, gender, sexuality, and pain. She has been collaborating with Coven Berlin since 2014.